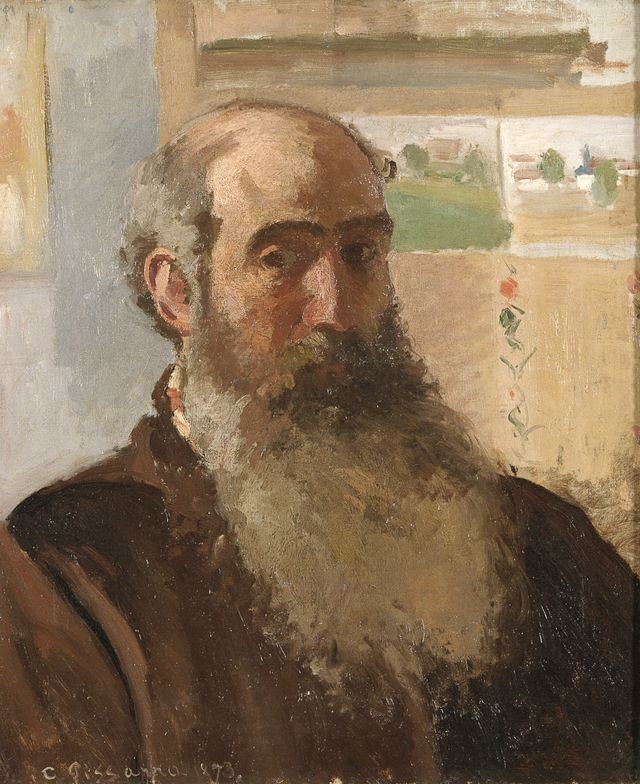

Camille Pissarro retrospective coming to Denver Art Museum

Camille Pissarro’s retrospective is coming to the Denver Art Museum (DAM), and the Mile High City is the only U.S. venue to exhibit the first major show of the “Father of Impressionism” in 40 years. On Oct. 26, the DAM will open “The Honest Eye: Camille Pissarro’s Impressionism,” the latest in its autumnal series of blockbuster exhibitions.

The uplifting exhibit of almost 100 works presents Pissarro as a colorful art history character introduced through his dazzling paintings and also excerpts from his archive of personal letters. At a tumultuous time for many Americans, Pissarro inspires as a free-spirited and optimistic artist able to see harsh reality while believing the world can and should be a better place.

“Pissarro was a cool guy. He’s the most interesting of all, the one I’d most like to meet,” said the DAM’s director, Christoph Heinrich, no stranger to the Impressionists. Heinrich has authored books about the Impressionists and co-curated the DAM’s major Monet show in 2019-2020.

“Pissarro was a true cosmopolitan, and that makes his life so interesting,” Heinrich said. “There was the belief that we are all in it together. Pissarro shows people in their dignity. ‘Respect’ might be an old-fashioned term these days that nobody wants to take seriously, but Pissarro shows us respect for very different environments and approaches to life. There is this true humanist stripe in all of his work and all of his statements, and how he looked at life is absolutely remarkable.”

A game-changing gift of Impressionist paintings

“The Honest Eye” shows through Feb. 8, 2026, exhibiting some of the most important paintings of Pissarro’s oeuvre, some never seen in the U.S. Befittingly, the DAM will mount the exhibit in the Hamilton Building — a 146,000-square-foot Daniel Liebeskind-designed, titanium-clad, origami-shaped structure named for the late Frederic C. Hamilton.

In 2014, Hamilton and his wife, Jane, bolstered the DAM’s permanent collection with a donation of their 22 Impressionist paintings. “That bequest was really a game-changer for us,” said Heinrich. “This is a very good example of how a permanent collection can drive an exhibition. I truly believe if we hadn’t received the Hamilton paintings, we wouldn’t have tackled the Monet show, nor would we have done this Pissarro show. The ability of museums to do certain projects is driven by the curiosity of what we have in our collection. The richer and more comprehensive the permanent collection gets, the more opportunities.”

Heinrich sat for an interview in his office together with the DAM’s senior interpretive specialist, Lauren Thompson, and Angelica Daneo, co-curator of both the Monet and Pissarro shows.

Daneo said, “Pissarro had a hopefulness. He knew turbulent times with personal and economic difficulties, political tensions. Yet through his paintings, his letters, his actions, he showed an unwavering hopefulness and a willingness to go on. There’s a lot to learn from Pissarro — more than from other artists who are more guarded — something very inspiring one can apply to wherever they are in life.”

The DAM’s Pissarro show spotlights a quintessentially Impressionistic painting, one from the Hamilton collection, “Spring at Éragny” — “Definitely one of my darlings,” Heinrich said.

Thompson said, “It’s one of my favorites. It’s luminous. It’s joyful. And the figures in the painting are probably his wife, Julie, and his children.”

In many ways seen and unseen, the exhibit highlights the value of relationships — Pissarro’s relationships with his family, peers and his working-class neighbors depicted in his rural paintings, as well as, naturally, his painterly relationship to landscape, to light. Pissarro’s importance in the art scene of his time is evidenced by his friendships with other celebrated artists: Claude Monet, Paul Cezanne and Paul Gauguin, Edgar Degas, George Seurat, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and the American, Mary Cassatt.

The exhibit’s many sponsors include Barbara Bridges — an educator and entrepreneur who founded Women+Film and formerly chaired the board of the Women’s Foundation of Colorado. Bridges, also an Impressionist fan, praised Pissarro’s leadership. “Camille Pissarro is known as the ‘Father of Impressionism,’ partly because he was a bit older than the others, but also because he acted like a father in holding the group together and encouraging the other members,” she said.

This past summer, Bridges saw the Pissarro show in Potsdam, Germany, at the Museum Barberini — the only other venue for the exhibit. “It’s fabulous. In this exhibition people will learn about Camille Pissarro. It takes us from his earliest paintings through the stages of his life’s works,” Bridges said. “I think people will love it!”

Pissarro painted and lived authenticity

Heinrich spoke to the exhibit’s title: “The Honest Eye.” He said, “What strikes me is Pissarro’s striving for authenticity. Pissarro wanted to paint exactly what his eyes were seeing at this moment. This authenticity is a striking motif in his whole life. He’s transferring what he sees, not editing. I find that refreshing in a time when things are Photoshopped or edited or an AI-altered image that loses the core. Pissarro’s striving for giving a picture that is authentic, giving an experience that is authentic still has something to teach us today.”

Heinrich and Daneo began planning the Pissarro show in October of 2019, the day after opening the Monet show — also a collaboration with Museum Barberini. The director and the curator realized the collective holdings of the two museums included more than a dozen Pissarro artworks could provide a foundation for this retrospective. The DAM also will show Pissarro works from American museums such as the National Gallery in Washington, DC, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. International lenders to the exhibit include the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the Muse’e d’Orsay in Paris and the National Gallery in London.

Daneo said, “Some of the loans visitors will see are something I am pleasantly surprised by — something that needs to be celebrated.”

Pissarro the person, Pissarro the painter

Like one of his pointillist canvases composed of countless daubs of paint synthesized as a whole, Pissarro presents as a man of many aspects. Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro was born in 1830 to well-heeled Sephardic Jewish parents of French and Portuguese extraction living on St. Thomas, an island then part of the Dutch West Indies. Pissarro never used his Hebrew names.

“He was fiercely secular,” Thompson said.

In the exhibit, the DAM devotes a gallery to Pissarro’s early, lesser-known works inspired by his time living in the Caribbean and Venezuela. Pissarro broke ranks with the family business to become an artist rather than a merchant. He married the family’s maid and established his family in France. Significantly, Pissarro was the only painter to show in all eight Paris Impressionist exhibitions.

Pissarro engaged with literature, poetry and politics. He spoke French, Spanish and English. Pissarro consistently recreated himself and varied his subject matter. The exhibition includes landscapes, cityscapes, harbor paintings, portraits, figures and still-life works. Pissarro painted not only romantic pictures, but also the pork butcher, the poultry market, the brick yard. He painted not the bourgeoisie, but the washer woman, the shepherdess, haymakers, peasant girls and gardeners.

Pissarro painted in oils on canvas, watercolors and pastels on paper. He toggled between Impressionism and Pointillism and at one point melded the two. He sketched. He drew political caricatures. A portion of the exhibition presents Pissarro’s silk fans painted with gouache. He experimented with ceramics and printmaking.

“He had the curiosity to reach out and be interested,” Heinrich said.

Pissarro’s letters reveal the man

Pissarro also distinguished himself by penning thousands of letters to his family, his art dealer and fellow artists. Drawing from this trove of source material, the DAM team patched together details from the painter’s life presented in the exhibit.

“It was a real privilege to start with the letters, the words of the artist. Pissarro pours himself into his letters and doesn’t shy away from sharing his ideas. That allowed us to bring out the human component. ‘Freedom’ is a big motif throughout his letters. He seeks to be absolutely free: freedom of thought and freedom to make choices in life, which he did, but also freedom in art is something he’s consistent about,” Daneo said. “Pissarro felt like an outsider, but his outsider status contributed to his greater experimentation in life and in [painting] styles. He believed he shouldn’t feel bound.”

Thompson said some of Pissarro’s letters were translated for the first time into English. “A deeper dive into his correspondence reveals the man: his worries, complaints, medical issues, his hopes, what’s going on with the family. We find his personal philosophies, politics, local gossip,” she said.

“Ultimately, he was an optimist and maintained a sense of optimism, through challenging personal and professional situations. Three of his children died. He fled the Franco-Prussian War. The Dreyfuss affair happened in Paris,” Thompson added. “In a letter to his landlord, he said 20 years of his life’s work had been destroyed in the war, but ultimately he wanted to get back to work.”

Pissarro valued the liberty of artistry

Heinrich said, “Pissarro believed art is the only and unique profession where you’re free. You decide what you’re doing. You’re not a boss to somebody, and you don’t have a boss. It’s not work that you do one part of it and somebody else finishes it. Only an artist is completely free and self-determined,” Heinrich said.

Pissarro’s insistence upon freedom did cost him: “There’s a joke that he painted cabbages and his wife cooked them,” said Heinrich. “They had hardship.”

Pissarro never realized much financial reward from his art, unlike his friend Monet, who granted Pissarro a loan for his home outside Paris. Yet in 2014, at auction, Pissarro’s “Le Boulevard Montmartre, Matinée de Printemps” fetched $32.1 million.

In closing, Thompson said, “Pissarro wrote that all an artist should wish for is to find a kindred spirit to understand him. We invite visitors to be those kindred spirits.”