Colorado man with a big heart gets a new heart – literally

To John Babiak, every person in the world is a friend.

How appropriate, then, that two people he had never met saved his life.

This August, the coach and former science teacher found himself on his 66th birthday in an intensive care unit with a grim diagnosis – his heart was failing.

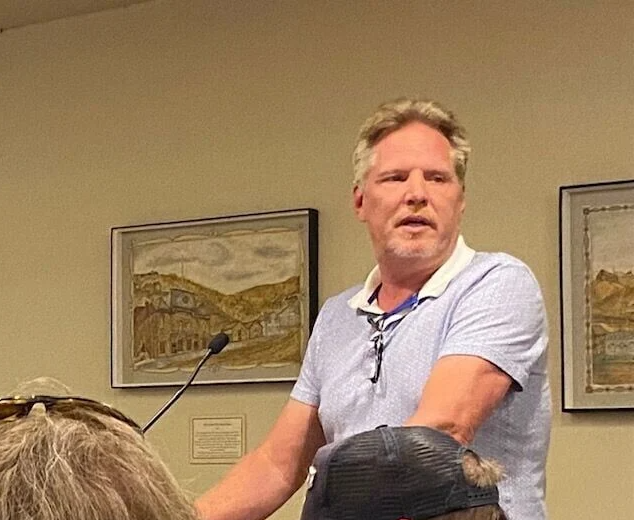

“The whole team thought he had no way to function,” said cardiothoracic surgeon Michael Cain, who performed the heart transplant.

“He was quite sick with dangerously abnormal heart rhythms and was also in cariogenic shock.”

The Englewood man’s heart could no longer squeeze hard enough to keep blood circulating through his other organs.

The self-described “Old Hercules” would likely die without a new one.

Babiak studied the screening process and made it his mission to convince a team of social workers, cardiac surgeons, pharmacists and infectious disease specialists that he was a solid candidate for a new heart.

He passed in five of the six categories – except the one stipulating he must have a full-time caregiver for 90 days following the transplant.

Babiak has no biological family nearby. But he has hundreds of friends, and he needed one person to step up – a serious commitment for people with full lives.

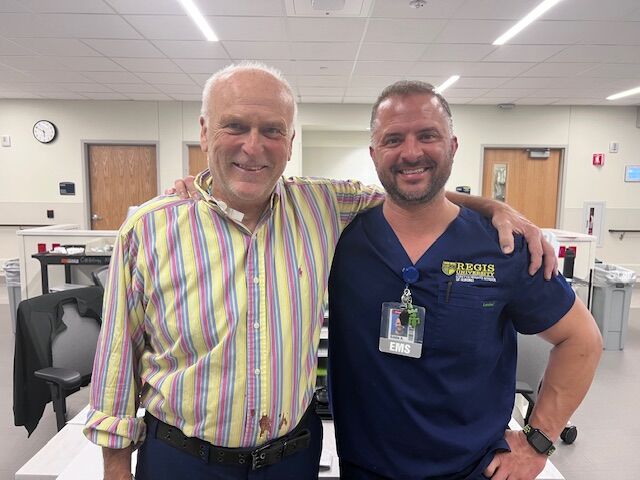

A Cardiac nurse, whom Babiak barely knew, asked him why he looked so depressed. Eddie Asher was on his final clinical rotation for nursing school.

“After he told me the story and the requirements, it melted my brain,” said Asher, who lives in Thornton. “The hospital was like, ‘Sorry dude. You don’t have friends. Just go die, I guess.’ We had a spare bedroom. I called Dana and before I was finished, she said, ‘Yep.’”

Babiak, who is never at a loss for words, could barely speak.

On Sept. 17, he moved into the hospital to await a donor. Two days later, he described the moment the attending nurse entered his room.

“She looked into my eyes and said, ‘Mr. Babiak, we found a heart for you!’ I said, ‘Right now?’”

By 10 p.m., the beating heart of a 20-year-old Idaho man who had just died was in his chest.

After the surgery, Babiak was determined to get back to his life. He spent only six days in the hospital recovering.

Cain, the surgeon, noted that his “energy for life” was key to getting him back on his feet after a taxing operation, which usually requires a two-week hospital stay.

For Cain and his transplant assessment team, a patient’s age is “not a hard cut-off.”

“We look at everyone as an individual,” he said.

Babiak was in the best of hands, as UC Health University of Colorado Hospital reached a milestone of 10,000 organ transplants this month.

In 1963, Dr. Thomas Starzl, often referred to as the father of modern transplantation, performed the world’s first successful human liver transplant there. His patient was a 44-year-old janitor, who received the liver of a 55-year-old veteran who had just died of a brain tumor.

ENERGIZER BUNNY

Friends describe Babiak as everyone’s guardian angel and an Energizer Bunny.

The former Denver Public Schools science teacher had kept his students engaged in STEM by channeling Steve Martin and Mister Rogers.

When his failing heart forced him to leave teaching, he taught himself photography and was eventually offered jobs that often take a lifetime of experience to procure.

Today, he travels with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. He is also the Colorado Rapids’ photographer.

Always an optimist, he is fond of sayings, such as this: “Today, I am full of glee.”

The son of World War II immigrants who fled Ukraine in 1945, Babiak dedicated his life to “the betterment of humanity” in honor his parents, who he watched struggle living in America.

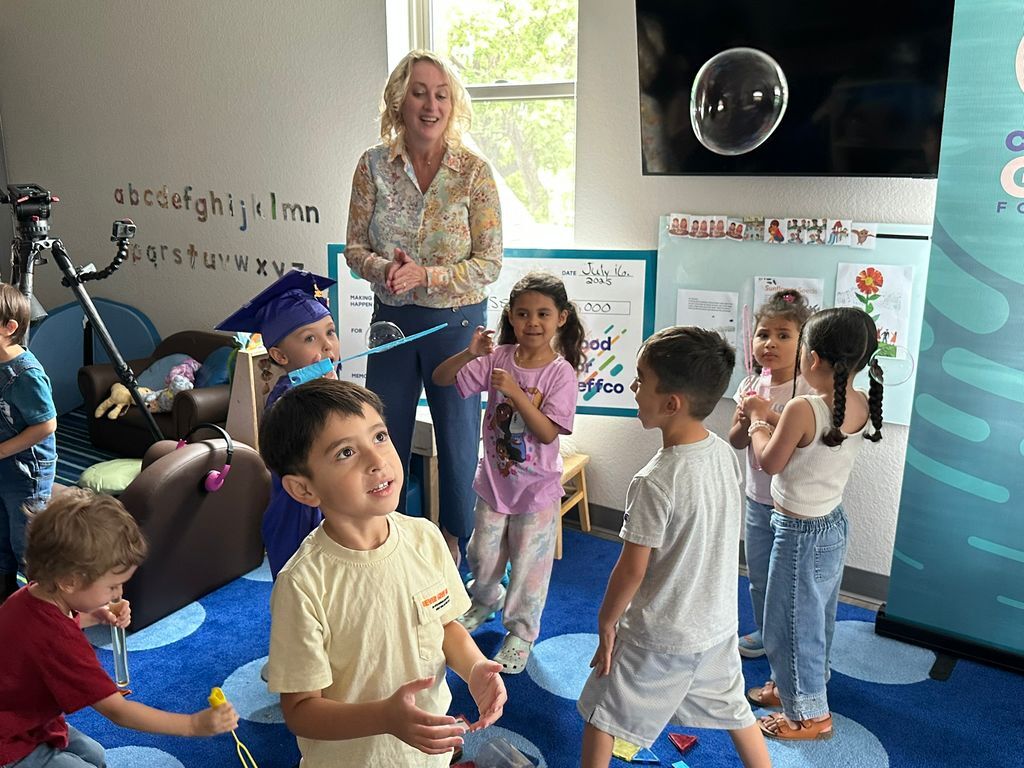

In their honor, he has taken seven trips on his own, at first to serve food with the World Central Kitchen and then, realizing that the people who need him the most are the youngest, with the most vulnerable victims of war.

So, the veteran soccer coach focused on introducing spiritual healing through recreation.

In Ukraine, he traveled to towns, where he knew children were displaced, traumatized and orphaned by the war. Everywhere he went, he knocked on the doors of orphanages, church doors and youth groups with four words for the administrators: What do you need?

Because the exchange rate is 24 Hryvnias to a dollar, he can buy a lot.

He purchases ping-pong paddles, bicycles, soccer astro-turfs and goals. He organizes a field day and bills it as the Olympics of the orphanage. Then he buys medals and gives one to each child.

During his most recent giving trip this past spring, he rolled up his sleeves and fixed a peeling empty pool at an orphanage in Mukachevo. The village is located in southwest Ukraine near Hungary, where many war survivors from the Eastern side of the country often end up.

“The kids asked for goggles. I bought the sportiest goggles, and these kids were over-the-top happy,” he said.

The beating heart of a stranger has given Babiak renewed purpose.

Last Friday, he played racquetball, served up volleyball on Saturday and flew to Los Angeles to shoot the pro football game between Tampa Bay and the Rams.

In a text accompanied by an arm-in-arm selfie with a human in a Ram costume, he wrote: “I’m strong enough to walk around SoFi stadium with three cameras for at least a dozen times. Another milestone!”

The next day, he visited a park and provided a pre-Thanksgiving feast to the homeless people who gather there – home-made peanut butter sandwiches, with a carton of milk.

The last 60 days have been busy for Eddie Asher and Dana Ritterbusch.

Besides taking Babiak in, they got married. Ritterbusch is working toward her master’s degree in sleep medicine through an online program at Oxford University. Asher, a Marine reservist who served three tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, finished his rotation and now has a position at UC Health.

The newlyweds agreed that the decision to harbor a stranger was impulsive, one made not with their brains, but with their hearts.

“Is it convenient? No absolutely not. If this is the hardest thing that we do, why wouldn’t we do it?” Ritterbusch said.

“Someone shouldn’t be put in a position where they will be left to die because they can’t care for themselves,” added Dana. “John goes out of his way to do so much good in this world, there’s going to be a trickle down. I hope it inspires someone to behave like a community.”

Babiak’s mystery donor family is grieving, so he will save contact with them for a gentler time because “me coming into the picture would be premature.”

He has one more month to stay in Asher’s extra room.

On Christmas Day, Babiak will to return into his Englewood home, and come May, he will go back to Ukraine to continue his crusade – helping kids in a precious race for time.

This Thanksgiving week, he may give his new heart permission to slow down a few ticks.

“Thanksgiving will be extraordinary,” he said. “It’s not like Dana and Eddie and I have been pals forever. That’s a miracle. I feel like I’m walking in a miracle every day.”